- Share via

Artist David Hockney was a driver: after visiting and then moving to Los Angeles in 1964, he zipped around the Hollywood Hills in his red 450 SL Mercedes, perhaps to Chateau Marmont, his spot in Malibu or the studio at multimedia workshop Gemini G.E.L. on Santa Monica Boulevard.

“For David in the 1960s, Los Angeles was an enigma — a unique city different from his native London or even from New York City where he had his first encounter with ‘America,’” says his close friend and fellow artist Doug E. Roberts. The drives were a way not only to catalog the landscapes he would later paint but also to understand the way the sun affected the visual identity of the city. “Southern California has a different light than any place he had ever visited,” Roberts says.

Modernism Week, a biannual celebration of midcentury architecture and design, returns to the desert city Feb. 13-23.

If a friend were visiting for lunch at the beach, Hockney would take them on a “Wagner Drive,” something he devised as an opera-loving motorist. He’d drive up through Malibu Canyon to Mulholland Drive and then west to Decker Canyon, where he would time the turns and crests to the crescendos of the classical composition. “He’s always fooling around,” says Roberts. As he drove he’d fast-forward the CD in the player to match the view in order to maximize the drama of the landscape.

One of Hockney’s first drives to Los Angeles was a cross-country dash with a pal: Brian Epstein had written on a napkin in Chicago inviting Hockney to see the Beatles in Los Angeles in 1963. He and a friend drove straight from Chicago to California in order to make it to the Hollywood Bowl in time, napkin in hand as his ticket backstage.

Many of the places Hockney loved simply don’t exist the way they once did. For example, one of his favorite restaurants was a Japanese spot on the Sunset Strip, Imperial Gardens; it’s now the permanently closed Pink Taco Hollywood location, nestled beneath the Chateau Marmont.

Hockney also took long drives in order to find interesting landscapes to doodle. Many of these destination drawings, photocollages and paintings are being shown, some for the first time, at the Palm Springs Art Museum (PSAM). Through March 31, PSAM will have “David Hockney: Perspective Should Be Reversed, Prints From the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation” on view. The exhibition features nearly 200 works spanning over six decades of Hockney’s career — from his earliest etchings in the mid-1950s and ’60s to his recent experiments with iPad and photographic drawings — which underscore the artist’s innovative experiments as a printmaker.

There’s more to Palm Springs than swimming and sunbathing. From Midcentury Modern furniture to vintage caftans and handcrafted pottery, there is something unique to be found in the shops along Palm Canyon Drive.

Beyond Palm Springs — which Roberts described as more as a pit stop than a destination — Hockney was far more fascinated by what lay beyond. Like his famous photocollage “Pearblossom Highway” in 1986, which depicts an intersection along California Highway 138, north of Los Angeles, he much preferred a landscape he could draw, and often visited the Mojave and Joshua Tree to do just that. As Roberts put it, “For him [these drives] were adventures to find the obscure landscape in which to draw.”

Hop in your automobile, with your proverbial convertible top down, to go on some of Hockney’s favorite drives and see what inspired him so much.

The Mutual Life Building in Pershing Square

“Pershing Square was a natural destination for a first-timer to the city with no center,” says Roberts. “And the tall square high-rises of downtown were a perfect thing for a new visitor to paint.”

After reading “City of Night” by John Rechy, Hockney saw Pershing Square as a sort of fantastical queer destination — and in the 1960s, it very much was. Many of the International Style buildings in downtown L.A. inspired a handful of sketches providing a glimpse into Hockney’s first impressions of the city.

A lithograph of Hockney’s famous 1974 drawing “Pacific Mutual Life” features the historically preserved PacMutual building with a large clock and the same palm trees lining the plaza. While the old graphic clock is gone and the plaza‘s design has been radically changed, this building still stands in DTLA’s Pershing Square.

The pool at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel

Looking out the plane window as he flew into Los Angeles for the first time, Hockney became enamored with the dozens of blue swimming pools he spied from above. These little luxuries would become a Hockney calling card and subject of several works, including “Gregory in the Pool (Paper Pool 4)” (1978) and “Pool Made With Paper and Blue Ink for Book” (1980), both of which are on view at PSAM.

His fascination with California began with drawing its water — from the ocean to city fountains — driven by his interest in the way light danced on the surfaces of pools. Painting the bottom of the Tropicana pool at the Roosevelt Hotel was a spontaneous favor for a friend who worked at the hotel — one that became a permanent fixture at the famous hotel in Hollywood.

As the story goes, Hockney appeared on deck with a bucket of blue paint and a broom affixed with a paintbrush to get the job done. To this day, when the pool is drained, the hotel retouches the lines, refreshing Hockney’s iconic blue half-moon marks every year or so.

Hollyhock House, Egyptian Theatre, Huntington Library. A number of L.A.’s most inspiring structures went up in the 1920s and they’re enduring parts of the area.

The Santa Monica Boulevard strip in West Hollywood

Santa Monica Boulevard, a major thoroughfare that runs through West Hollywood and connects much of L.A., features heavily in the cultural and visual landscape that Hockney has often explored. Hockney’s relationship to this area is most visible in how he captured Los Angeles’ unique sense of place — bright light, urban architecture and laid-back California living.

Though it’s changed significantly since Hockney’s era, the long stretch between Western and La Cienega is immortalized in a massive painting series aptly titled “Santa Monica Boulevard (1978–80).” His signature flat perspective celebrated the colorful modernist boxy buildings along the famed thoroughfare in 1960s West Hollywood, featuring a quotidian sidewalk scene of an old auto shop and other storefronts in vibrant teal, orange and yellow hues.

The Chateau Marmont

In the mid-’70s, prior to the acquisition of his house up in the hills, Hockney had an extended stay at the Chateau Marmont for several weeks while working on the series of lithographs of “friend portraits” at Gemini G.E.L. (Graphic Editions Ltd.), a renowned print workshop on Melrose Avenue. Since it was built in 1929 as the first earthquake-proof building, the Chateau Marmont has long been home to iconic out-of-towners and chic Angelenos.

The Chateau figured prominently in Hockney’s personal life and in his compositions: One of his famous paintings, “House Behind the Chateau Marmont” (1976), features the Spanish Revival-style house that peeks above from just behind the Chateau, while a 1967 lithograph featuring an intimate moment between friends, “Henry and Christopher in the Chateau Marmont Hotel, Hollywood.” Both paintings are at the PSAM exhibition.

Gemini G.E.L.

Established in 1966, Gemini G.E.L. was Hockney’s main printmaking studio in L.A., collaborating exclusively with him to produce and sell prints and editions of works. The famed publisher was also an artists workshop and produced legendary prints by some of Modern art’s most prominent artists, including Frank Stella, Robert Rauschenberg and, of course, Hockney. Among his early L.A. projects was a suite of prints featuring portraits and scenes of his friends sitting around the Chateau, in their apartments, lounging on couches and pools, and sleeping in together — aptly named “Friends” (1976) — that he worked on while living at the Chateau.

Hockney continued his lithographic and print work through the 1980s and still works with the studio to produce his iPad images and subsequent drawings. Many of his drawings and prints of friends were set up in the studio space at Gemini, making it a more subtle but historic spot for Hockney’s legacy. If those walls could talk!

Nichols Canyon Road in Hollywood

In 1963, Hockney bought a house in the Hollywood Hills, and drove up and down the steep, winding roads as he went to work, to parties, dinner and exhibitions with friends and colleagues. Nichols Canyon was the road less traveled; Hockney preferred the drive downhill to Sunset Boulevard via Nichols for its solitude and serpentine charm.

In the 1980s, he painted the route by memory in “Nichols Canyon” (1980), which depicts a flattened perspective of the road from the hilltops to Sunset, capturing every hairpin turn and the roadside flora and fauna in a cascade from the top to the bottom of the canvas. Take the vertical loop to the top of the hill and stop at Trebek Open Space or Bantam Trailhead for sweeping views of Hollywood and beyond. Be careful of fawns and other skittering critters as you drive.

The top of Rising Glen Road

Another road Hockney liked to cruise was Rising Glen Road, just over from the tony Bird Streets neighborhood, where a friend of his lived nestled in the hills. He made much work at his friend’s house, spreading photos for collages and drawings all across the floor and dinner table.

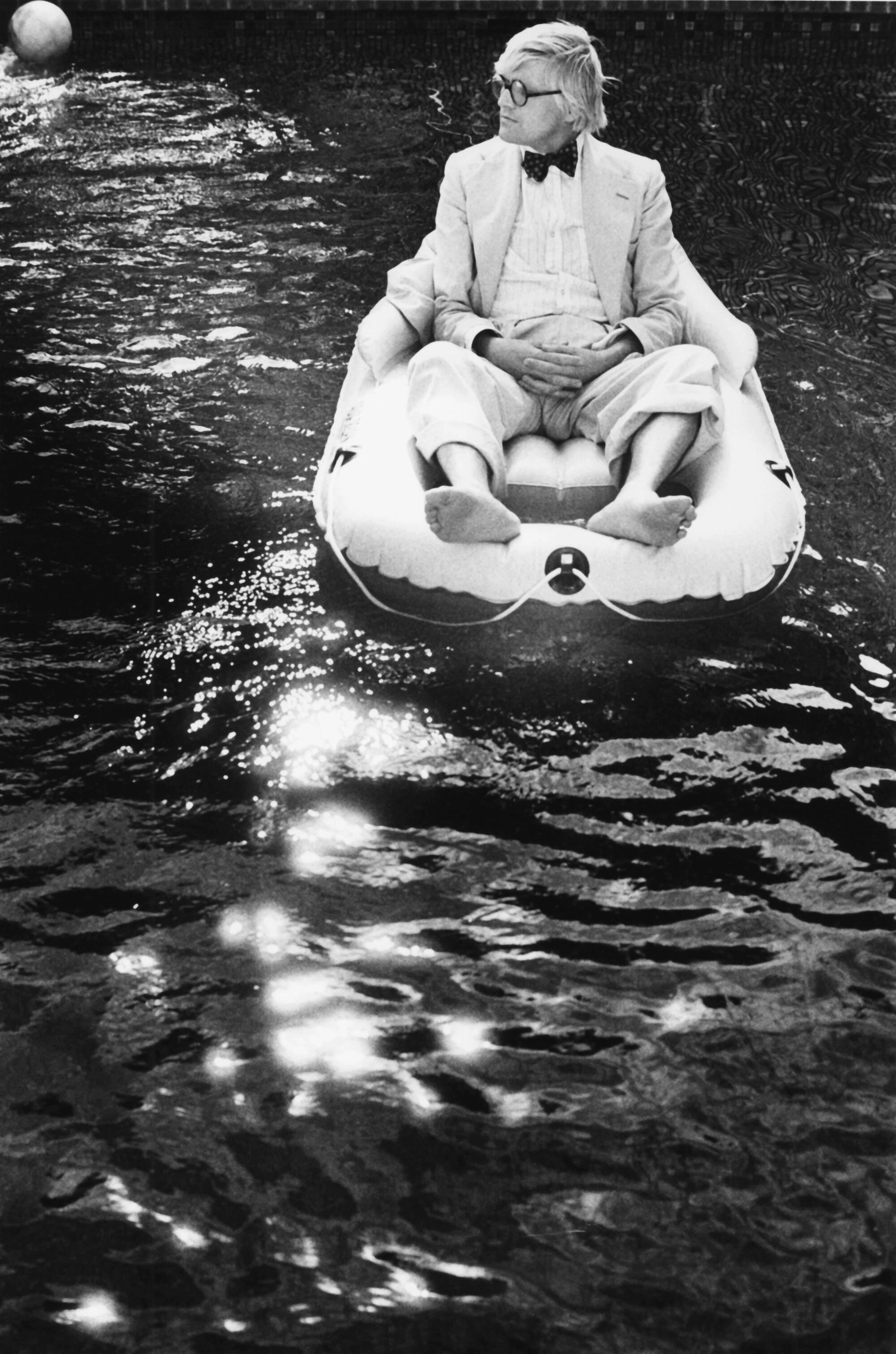

In addition to rare lithographs, Hockney’s PSAM show includes a personal 1978 photograph of the artist, which features him lounging in a pool, looking over the view from a house that sits on Rising Glen Road. For the same perspective, spiral up from Sunset Plaza Road or Thrasher Avenue, and drive up to the tip-top of Rising Glen Road — be mindful of the neighbors while you wind your way up.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.